|

N° 6894

"H I L D A" (S.S.)

The Merchant Shipping Act, 1894.

In the matter of a formal

investigation held at Caxton Hall, Westminster, on the 1st , 2nd

and 8th day of February 1906, before R.H. B.MARSHAM, Esq., assisted

by Captain RONALDSON, Commander CABORNE, C.B., R.N.R., and Vice Admiral O.

CHURCHILL, into the circumstances attending the loss of the British steamship

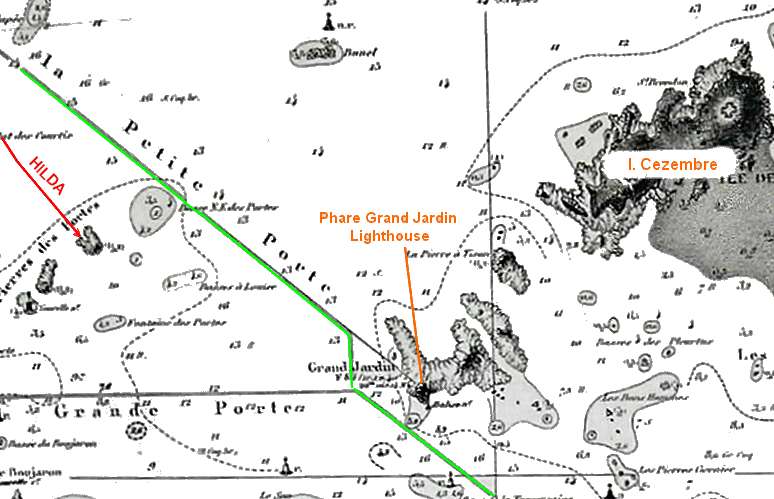

"HILDA" at or near the Pierres des Portes, northwest coast of France, on the 18th

day of November, 1905, whereby loss of life ensued.

Report of Court

The Court having carefully inquired

into the circumstances attending the above-mentioned shipping casualty, finds

for the reasons stated in the Annex hereto that the said casualty was caused by

the Hilda striking on one of the Pierres des Portes rocks, outside St. Malo,

during a snowstorm, but in the absence of definite evidence, owing to the fact

that all those who could have thrown light upon the matter were drowned, the

Court is unable to express an opinion as to how she got there.

Dated this 12th day of

February, 1906.

R.H.B.

Marsham,

Judge

We concur in the above Report

A.Ronaldson,

W.F.

Caborne,

O.Churchill, V.Adm.,

Assessors

Annex to the Report

This inquiry was held at the Caxton

Hall, Caxton Street, in the city of Westminster, on the 1st , 2nd

and 8th day of February, 1906.

Mr Pickford, K.C., and Mr A.D.

Bateson (instructed by the sollicitor for the department) represented the Board

of Trade, while Mr Butler Aspinall, K.C., and Mr J.A. Simon, M.P. (instructed by

Mr Sam Bircham, sollicitor to the London & South Western Railway Company, and

Messrs Clarkson, Greenwell and Company), appeared for the owners, Mr D. Stephens

(instructed by Messrs Woodhouse and Davidson) for the executor and children of

the late Mr and Mrs Wellesley, Mr Maurice Hill (instructed by Messrs Broad and

Cheston) for the representatives of the late Colonel Follett, Mr Ryland (Messrs

Woodcock, Ryland and Parker) for the relatives of Rev. Dr. Stanley, Mrs Stanley,

Miss Norah Stanley, and a maid, and Mr Jones (representing Messrs Peake, Bird

and Collins) for the Honourable Henry Cavendish-Butler, husband of the late

Honourable Mrs Butler.

The "Hilda" official number 86327,

was a screw steamship built in iron in 1882, at Glasgow, by Messrs Aitken and

Mansel. She was registered at the port of Southampton, and was the property of

London and South Western Railway Company, having its principal place of business

in London and was under the management of Mr Tom Mitchell Williams, the

company's dock and marine superintendent, at Southampton, who was designated as

the person to whom the management of the vessel was entrusted by and on behalf

of the owners, by advice under the seal of the said company received on the 1st

of January, 1902.

The dimensions of the vessel were

as follows :- Length 235.6 ft. ; breadth 29.1 ft. ; and depth in hold from

tonnage deck to ceiling at midships, 14.2 ft. ; her gross tonnage being 848.06

tons, and her registered tonnage, 378.36 tons.

She was propelled by compound

engines of 220 nominal horse-power, built by Messrs John and James Thomson and

Company of Glasgow, in 1882 and designed to give her a speed of 12 knots, the

cylinders being respectively 37 ins. And 69 ins. And the length of stroke 39

ins. ; and she was fitted with two steel boilers, made by Messrs Day, Summers

and Company, of the Northam Iron Works, Southampton, in 1894, and having a

working pressure of 85 lbs. to the square inch.

She had five water-tight bulkheads

; both hand and steam steering gear were provided and she had been furnished

with an installation of the electric light in 1894.

She carried six boats, namely, two

lifeboats of the aggregate capacity of 587 cubic ft. and capable of

accommodating 57 persons, two boats of the aggregate capacity of 321 cubic ft.

and capable of accommodating 40 persons and two other boats capable of

accommodating 57 persons. These boats were supplied with all requisite

equipments and were fitted with Messrs Hill and Clarke's patent disengaging

gear.

With regard to other life-saving

appliances, she had 12 lifebuoys and 318 lifebelts, 192 of the latter being

placed in the cabins, 100 being stowed on battens under the forecastle, and 26

being reserved for the use of the crew.

In accordance with the Board of

Trade regulations, she carried a signal gun and the proper number of cartridges,

rockets and blue lights.

In the way of navigating

instruments, she had three compasses, namely, one (Lord Kelvin's patent) on the

bridge, which was the standard compass by which the courses were set and

steered, and two others (one of them being a spirit compass) situated one on

either side of forward of the after steering wheel, and she was also furnished

with a "cherub" taffrail log, and the ordinary hand and deep-sea lines.

The compasses were last regularly

adjusted by Mr J. Blount Thomas, compass maker and adjuster of Southampton, in

May 1894, but since then, it was stated they had been examined and overhauled at

fixed periods, the vessel subsequently making a trial trip to ascertain that all

was in order. Moreover, on the 26th April, 1905, both the master and

the then chief mate signed a declaration as to the good condition of the

compasses, and their knowledge of their errors, as required by the Board of

Trade when granting a passenger certificate.

Admiralty charts and Part II of the

Channel Pilot, found by the master, were on board and the company further

supplied the steamer with a copy of the "Annuaire des Marées des Côtes de France

pour l'an 1905", published by the French "Service Hydrographique de la Marine".

On the 30th of May,

1905, the "Hilda" which originally cost £33,000, and at the time of her loss was

valued at £12,000, half of that amount being covered by insurance and the London

and South Western Railway Company taking the other moiety of the risk, was

granted a passenger certificate for Home Trade limits (such limits including of

course the Channel Islands and St. Malo), such certificate to remain in force

until the 15th of May, 1906 and the number of passengers for which

she was licensed being 566.

A few words should now be devoted

to the personnel of the vessel.

The master, Mr William Gregory,

entered the company's service as an A.B. about the year 1869 and gradually

worked his way up, becoming successively second mate in 1871, chief mate in 1874

and master in 1880. He was described by several witnesses as a man proverbial

for his caution and one whom passengers specially selected to travel with, and

in addition to a Home Trade master's certificate of competency (N° 101888), he

possessed pilotage licenses for Southampton and Jersey. Of his experience in

connection with this particular trade it is not necessary to say more than

that, during his time as master, he had entered the harbour of St. Malo on about

one thousand occasions.

The chief mate, Mr Albert Edward

Pearson, also entered the company's service as an A.B. in 1890, becoming second

mate in 1899 and chief mate in 1904. He was possessed of a Home Trade master's

certificate of competency and held pilotage licenses for Southampton and Jersey.

The second mate, Mr E. Greaves joined the company in 1904 and possessed a

Foreign Trade master's certificate.

The pilot, Mr J.W. Courtman who had

special knowledge of the Channel Island waters and the coast of France in the

neighbourhood of St. Malo, had been in the service of the company for about

four years. He held a pilotage license for Jersey, but not for St. Malo.

However, by an agreement entered into by the representatives of the company and

the pilots of St. Malo, St. Servan, St. Cast and Cancale, the company's steamers

are allowed to dispense with the service of local pilots.

Coming to the narrative of the

voyage, the "Hilda" left Southampton at 10 p.m. of the 17th of

November, 1905, bound to St. Malo with about 109 passengers and about 10 tons of

general cargo, manned by a crew of 28 persons all told (including the pilot),

and under the command of Mr. William Gregory. Her approximate mean draught

would be about 10 ft. and she would be trimmed about two and a-half ft. by the

stern. The proper sailing time was 8.15 p.m., in which case the vessel would

have been due at her destination about 9 o'clock of the following morning, but

the master delayed his departure for an hour and three-quarters owing to the

presence of fog and did not leave until it lifted.

Yarmouth in the Isle of Wight, was

reached shortly after 11 p.m. and further fog being encountered, the master

anchored off that place until about 6 a.m. of the 18th of November

when the voyage was resumed.

At 0.30 p.m. the steamer had passed

through the Race of Alderney, the weather at the time being fine and clear, with

a light easterly wind, James Grinter, A.B., the sole survivor of the crew, to

whom the Court is indebted for the narration of events, now left the deck, it

being his watch below. About 2 p.m. one of the other hands went below and told

Grinter that they were off Jersey and that the breeze was freshening, but the

latter had no knowledge as to the position at that hour. At 4.30 p.m. Grinter

returned to the deck and it was then blowing hard from the eastward, there was a

heavy sea running and the atmosphere was very clear. At 5.10 p.m. he went n the

look-out on the bridge where were the master, pilot, and chief mate, and the

Grand Jardin light was then visible a little open on the port bow but he did not

know its compass bearing. The weather still remained clear but looked

threatening. About 6 p.m., the St. Malo leading lights were in sight, open to

the eastward of the Grand Jardin light and all the town lights and the light on

Cap Fréhel were likewise to be seen. About 6.30 p.m. the Grand Jardin light was

distant about half a mile, and bearing a little on the port bow. A heavy snow

squall now came along, shutting in all the lights and the master instantly

ordered the engines to be slowed down and the helm to be put hard-a-starboard

and the ship's head was brought to seaward. Grinter went off the look-out at

6.30 p.m. but remained on the bridge until 8.30 p.m., and during those two

hours, the "Hilda" was manoeuvring or dodging off the land, the weather being

squally and heavy snow falling. However, the Grand Jardin light was visible

every 10 or 15 minutes, between the snow squalls, but none of the other lights

could be distinguished. The first time the master saw the Grand Jardin light

after the snow commenced, he called the pilot's attention to the fact that the

ship was far enough to the eastward and the course was altered more to the

westward. Afterwards, when he saw the light, the master took bearings of it and

then went and consulted the chart. The lead, according to Grinter's evidence,

was not used prior to 8.30 p.m. That it was not used subsequently, the Court has

no evidence and therefore cannot attribute the loss of the vessel to its

non-use.

At 8.30 p.m., it was blowing strong

from the eastward, there was a very heavy sea and snow was falling heavily. The

master, pilot and chief mate were all still on the bridge when Grinter went

below at that hour, his watch on deck being over, and thence forward, there is

no information as to the navigational proceedings in connection with the

ill-fated "Hilda".

Approximately about 11 p.m. Grinter

who was asleep in his bunk, was awakened by the ship striking the rocks, and he

and the remainder of the watch below instantly rushed on deck and ran to their

stations on the bridge and at the boats. At this time, it was snowing hard, a

strong easterly wind was blowing and there was a heavy sea running. The master,

chief mate and second mate were on the bridge, but Grinter did not notice the

pilot, probably owing to its being very dark.

The master ordered the boats to be

got ready, and the starboard lifeboat was lifted out of the chocks ; but it was

then discovered that it could not be lowered into the water on account of the

nearness of the rocks. For the same reason, the port lifeboat and the port

cutter were not available. The master gave orders for the starboard cutter to be

lowered, but when it was half way down, a heavy sea smashed the boat against the

ship's side, rendering it useless and turning it bottom up. About this time, the

foremast which had previously been seen swaying, went over the side.

While all this was going on, the

master had been alternately firing distress rockets and sounding the whistle.

The saloon passengers had

congregated round the after hatch, which was the most sheltered place on the

vessel, and the stewards and stewardesses were helping them to put the lifebelts

while the Breton onion-sellers gathered along the starboard side under the

bridge, were assisting one another in a similar manner. There was no confusion

either amongst the passengers or the crew.

An attempt was made to get out the

port quarter boat, but while this was being done, the after part of the ship

sank in the water, a heavy sea swept over her stern and everybody was washed off

the deck. Grinter was washed alongside the private cabin under the port main

rigging, which he managed to seize and climb up into, as did also the chief mate

and the cook ; the starboard main rigging being full of people who had succeeded

in obtaining refuge there, such as it was. Some two minutes later, or about ten

or twelve minutes after she struck , there was a crash and the "Hilda" broke in

two, at the same time, heeling over to such an extent as to put those who were

clinging to the eyes of the rigging into the water, and causing the loss of most

of the others. However, she righted again to an angle of about forty-five

degrees, although she subsequently rolled throughout the night. Only a few words

passed between Grinter and the chief mate who was as to the cause of the

accident, but the latter remarked to the former, "all gone ! not a soul left to

tell the tale !" and wished him goodbye. Grinter now climbed up on the gallows

of the masthead light, which remained burning until the morning although

latterly somewhat dimly, and called to the chief mate to get up higher, but he

was unable to do so. Some two hours after the vessel sank, the cook dropped into

the sea, and at about 6 o'clock the following morning, the 19th of

November, the chief mate died clinging to the mast. Throughout the night, it

only cleared once for five minutes and then the shore lights were visible but it

cam thick again, the heavy snow giving place to thick sleet.

Just before the chief mate died, a

pilot cutter sailed out past the wreck, but she was too far off for those on the

mast to attract her attention.

About 9.30 a.m., the s.s. "Ada" (Mr

Albert Edward Howe, master), belonging to the London and South Western Railway

Company, which vessel should have sailed for Southampton on the previous evening

but had been detained in port by the snowstorm, came out of St. Malo and

observing the men on the mast, sent a boat to rescue them, a feat which was

accomplished with considerable difficulty, although the wind had somewhat

moderated it was still blowing hard from the eastward and there was a heavy sea.

The chief mate, a fireman, and two Bretons were found dead in the rigging. About

the same time that the "Ada" sent her boat, a French pilot cutter which had

appeared on the scene, sent her boat also, and at great risk saved one of the

Breton onion-sellers who had spent the night on the forecastle of the "Hilda".

Unfortunately, the name of the pilot to whom this boat belonged, did not

transpire at the inquiry. The sole survivors consisted of James Grinter, A.B.,

and five Bretons who were conveyed to the hospital at St. Malo.

The position where the vessel

struck was on one of the Pierres des Portes rocks about six cables distant in a

W.N westerly direction from the Grand Jardin light, and about two cables, or say

four hundred yards, to the westward of the Chenal de la Petite Porte.

As it was high water at St. Malo at

9.53 p.m. on the 18th of November, the vessel must have stranded when

the tide had been falling for about an hour.

The first intelligence of the

catastrophe was conveyed to St. Malo by the "Ada", the signals of distress shown

by the "Hilda" not having been seen from the shore, although the London and

South Western Railway Company's employees were on the pier most of the night,

nor from the Grand Jardin lighthouse. Even if they had been seen from the Grand

Jardin, no information could have been conveyed during the night, owing to the

lack of telegraphic communication with the shore.

It is true that Mrs Eveleen

Grindle, widow of Mr G.A. Grindle, one of the passengers by the "Hilda" who was

staying at St. Malo, subsequently made a deposition before the Administrateur de

l'Inscription Maritime, of which the following is a translation :

"On Saturday the 18th at

half-past ten, I and my children went up to the top of the house in order to see

the lights of the 'Hilda' as she came in. During a few minutes, we saw the

lights and a minute or two afterwards, we saw several rockets 'fusées') - my

children and I counted six - and we all said : 'Oh that is the signal to show

that they are arriving' and then the lights disappeared, but we thought that the

boat had passed behind a house which is in front of this one. I ought to add

that we could see the lighthouse quite distinctly".

The court was informed that about

seventy bodies had been recovered and that most if not all of them, had

lifebelts on, secured by sailor knots.

The foregoing are the facts of the

case so far as they can be ascertained, but in the absence of direct evidence,

owing to the loss of all those who could have thrown light upon the matter, the

Court is unable to determine the cause of this most lamentable casualty and does

not feel justified in dealing with mere hypotheses.

The London and South Western

Railway Company rendered the Court every assistance in this inquiry, and it is

only fair to that corporation that two circulars issued by its marine

superintendent to the masters of its steamers should be quoted.

The first is dated at Southampton

the 9th of February 1898, and is as follows :

"I desire to call your attention to

practising your crew at fire and boat drill. I trust this matter has had your

continued attention, still I wish to remind you that the drill should take place

not less than once a month under your supervision, and at the same time you

should see all pumps, hoses, boats and gear in good working order. Please record

the drill in the ship's log, and inform me in your voyage report each time it

occurs."

These instructions appear to have

been duly carried out in the case of the "Hilda."

The second circular is dated at

Southampton on the 12th of June, 1899, and is as under :

"I am instructed by the directors

to send you a copy of the decision of the board of Trade assessors in the case

of the recent sad wreck of the "Stella", involving the unfortunate loss of so

many lives. I must particularly draw our attention to the answers given by the

Court on questions N° 13, 16, 17, 18, and 20. Several orders have been given

from this office to the captains at various times and I am again to impress

upon you that the first consideration under all and every circumstance is to be

the safety of the passengers carried in the company's steamers. Comment has been

made in the Press as to the company's vessels racing with steamers of other

companies to the Channel Islands. If any case of racing is proved I am

instructed to inform you that the captain responsible will be subject to

immediate dismissal. It is impossible to lay down any strict rules as to what

captains should do under varying circumstances, but in case of fog, soundings

must be taken and the speed so regulated that all possible risk may be avoided.

Under no circumstances whatever are any unnecessary risks to be run, either by

excessive speed or by attempting to take short cuts, but the vessels have to be

navigated by the correct and proper courses and by the various marks when

visible. Officers and men must always be at their posts, and a good and

efficient look-out kept both by the mates and men throughout the voyage ; and

whenever leaving or coming into port all hands must be at their posts for a

sufficient and proper time after leaving or approaching the port. It is the duty

of the captain to maintain strict discipline on the part of the crew, and not

to allow any unnecessary attention to passengers on his own part or the

officers or crew to interfere with the due and careful navigation of the ship.

Boat drill should be frequent, and every man must know his post. The boats must

be frequently and regularly inspected in order it may be seen that they are

fitted for every emergency and are so placed to as to be ready for use on the

shortest notice. The lifebelts must also be regularly overhauled at short

intervals. Be good enough to make this communication known to all chief and

other officers on board your ship, and acknowledge receipt by signing and

returning to me the annexed slip."

After the proceedings had

practically closed, a report from a diver, and the depositions taken at a French

Court of Inquiry were received, but they were of no additional material

assistance. One French deposition however, -that of Mrs Grindle - has been

quoted in the course of this Report.

At the conclusion of the evidence,

Mr Pickford, on behalf of the Board of Trade, submitted the following questions

for the opinion of the Court :

Questions

(1)

What number of compasses had the vessel, were they in good order and

sufficient for the safe navigation of the vessel ; and when and by whom were

they last adjusted ?

(2)

Was the vessel supplied with proper and sufficient charts, and sailing

directions ?

(3)

When the vessel left Southampton on the 17th November last,

(a)

Was she in good and seaworthy condition as regard hull and equipments ?

(b)

Was she supplied with the requisite boats and life-saving appliances ;

were the boats and life-saving appliances on board in good condition and ready

for use ?

(4)

What was the cause of the stranding and loss of the vessel on or near the

Pierres des Portes rocks outside of St. Malo shortly before midnight of the 18th

- 19th last ?

(5)

What was the cause of the loss of life ; was every effort possible made

by the master, officers and crew, to save life ?

(6)

Does any blame attach to Mr Tom Mitchell Williams, registered manager ?

The various legal representatives

then addressed the Court. Mr Pickford replied on behalf of the Board of Trade ;

and on a latter day - the 8th instant - the Court gave judgement as

above, returning the following answers to the questions submitted to it by the

Board of Trade :

Answers

(1)

The "Hilda" had three compasses, namely, one (Lord Kelvin's patent) on

the bridge, by which the courses were set and steered, and two others placed one

on either side before the after steering wheel. They were in good order and

sufficient for the safe navigation of the vessel, and were last adjusted by Mr

J. Blount Thomas of Southampton, in May, 1894. While the date of the last

regular adjustment was upwards of eleven years ago, the compasses had since been

examined and overhauled at regular periods by a competent person, and that

master and mate signed a certificate as to the condition and deviations of the

said compasses, as required by the Board of Trade when granting a passenger

certificate, on the 26th day of April, 1905.

Though, the Court has no reason to

suppose that there was any error in the compasses or that the casualty was in

any way to be attributed to them, it thinks that it is desirable that a ship

should be swung and deviations ascertained at more frequents intervals.

(2)

The vessel was provided with proper and sufficient charts, sailing

directions and tide tables. The charts used were the Admiralty ones.

It has been shown that in the case

of steamers belonging to the London and South Western Railway Company, the

masters are required to provide their own charts ; and while in this instance,

the Court has no reason to believe that the charts relied upon were not up to

date, and is quite convinced that this disastrous casualty was in no way

attributable to such cause, yet in its view it is better that owners should

supply all charts and sailing directions.

(3)

When the vessel left Southampton on November 17th last -

(a)

She was in good and seaworthy condition as regards hull and equipments.

(b)

She was supplied with the requisite boats and life-savings appliances.

The boats and life-saving appliances on board were in good condition and ready

for use.

(4)

The cause of the stranding and loss of the vessel on or near the Pierres

des Portes rocks, outside St. Malo, shortly before midnight of the 18th

- 19th November last, will never be definitely known, owing to the

fact that all those who could have thrown light on the matter were unfortunately

drowned. It was shown in evidence that Mr William Gregory, the master, an

experienced man who had made about one thousand voyages to St. Malo, was an

extremely cautious navigator ; that upon the passage in question which commenced

at 10 p.m. on November 17th, he delayed his departure from

Southampton by one and three-quarter hours on account of fog ; that owing to

further thick weather setting in, he afterwards anchored off Yarmouth, Isle of

Wight, until 6 o'clock the following morning ; that heavy snow prevailing he put

his vessel's head to seaward when off Le Grand Jardin lighthouse ; that, prior

to 8.30 p.m., when all knowledge of the navigational proceedings on board

terminates, he was observed taking bearings and consulting his chart, and that

immediately after the "Hilda" struck, he was seen on the bridge attending to his

duty. Under these circumstances, whatever may have been the real cause of the

disaster, the Court is not inclined to attribute it either to rashness or

negligence.

(5)

The cause of the loss of life was the inability to lower some of the

boats owing to the close proximity of the rocks, the smashing of another boat by

a wave while being lowered, the heavy sea running, the sudden manner in which

the vessel broke in two, and the intense cold of the night. From the evidence of

the survivors to the effect that after the vessel struck, there was no confusion

or disorganisation among the passengers or crew coupled with the fact that most,

if not all, of the bodies recovered were wearing lifebelts which, it was stated,

were fastened with reef knots ; the Court is of opinion that every possible

effort was made by the master, officers and crew to save life. From the

proceedings at a French court of Inquiry, it appears that no signals of distress

were seen from the Grand Jardin lighthouse during the night in question and,

even if they had been seen , the news of the catastrophe could not have been

conveyed to St. Malo, as it was stated that no telegraphic communication existed

with the mainland. As a matter of fact, the intelligence did not reach St. Malo

until the s.s. "Ada", also belonging to the London and south Western Railway

Company, which vessel left St. Malo for Southampton about 8.30 a.m. on the 19th

November, returned to the former port with the few survivors whom she had

rescued from the wreck with some difficulty by means of one of her boats.

A lady at St. Malo, the widow of a

passenger by the "Hilda", according to a deposition made at the same French

Inquiry, stated that she and her children saw from the top of their house some

lights and about six rockets at 10.30 p.m. of the 18th November, in

direction of the lighthouse, but the lights shortly afterwards disappeared.

(6) No blame attaches to Mr

Tom Mitchell Williams, the registered manager.

The Court wishes to express to the

French Government its great regret at the heavy loss of life of the subjects of

that nation, and to thank that Government for the valuable assistance given by a

pilot in rescuing at considerable risk one of those saved, and also for their

kindly help in this inquiry. The court also desires to state its high

appreciation of the extremely kind and considerate attention shown to the

relations of the English passengers and crew who were drowned, and of the care

and trouble taken in recovering the bodies. And the court also begs to convey

its deepest sympathy to the relatives and friends of all those, both French and

English, who met their deaths in this most deplorable disaster, which cost the

lives of about 130 persons.

R.H.B.

Marsham

Judge.

We concur,

A.

Ronaldson,

W.F.

Caborne,

O.

Churchill, Vice-Adm.,

Assessors.

|